Mining in North Midwest U.S.

The iron / copper range in

Michigan/Wisconsin/Minnesota is booming. There are copper and iron projects in

process. There is lots of concern on water and wastewater. Both biological and

membrane processes are on the table along with clarifiers and gravity filters.

U.S.

Taconite Mine Violations and Fines

Under current regulations, taconite mining wastes in Minnesota and Michigan are currently exceeding discharge limits for mercury, selenium, sulfates.

A survey of compliance records from 2004-2011, shows that modern taconite mines are chronic polluters. Moreover, most of these fines and violations have taken place under Minnesota’s ferrous mining law established in 1993. Is this a mining law we should use as an example for Wisconsin?

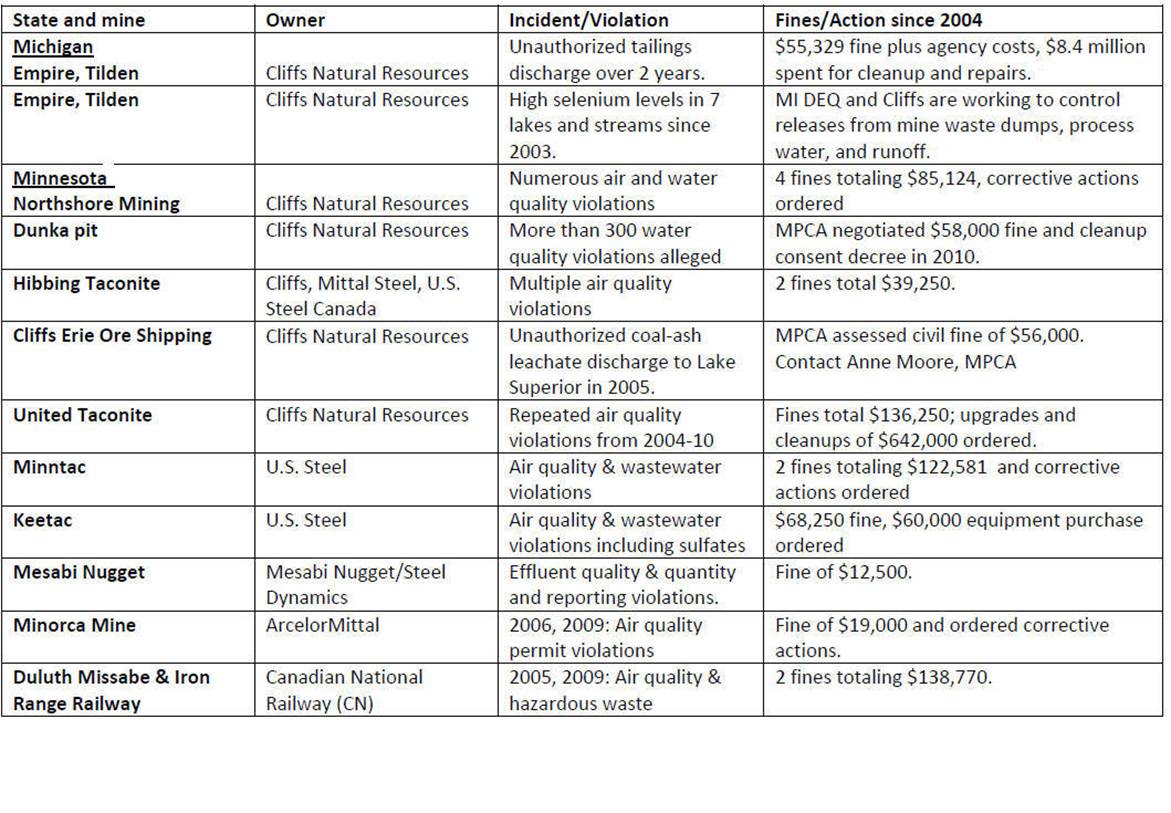

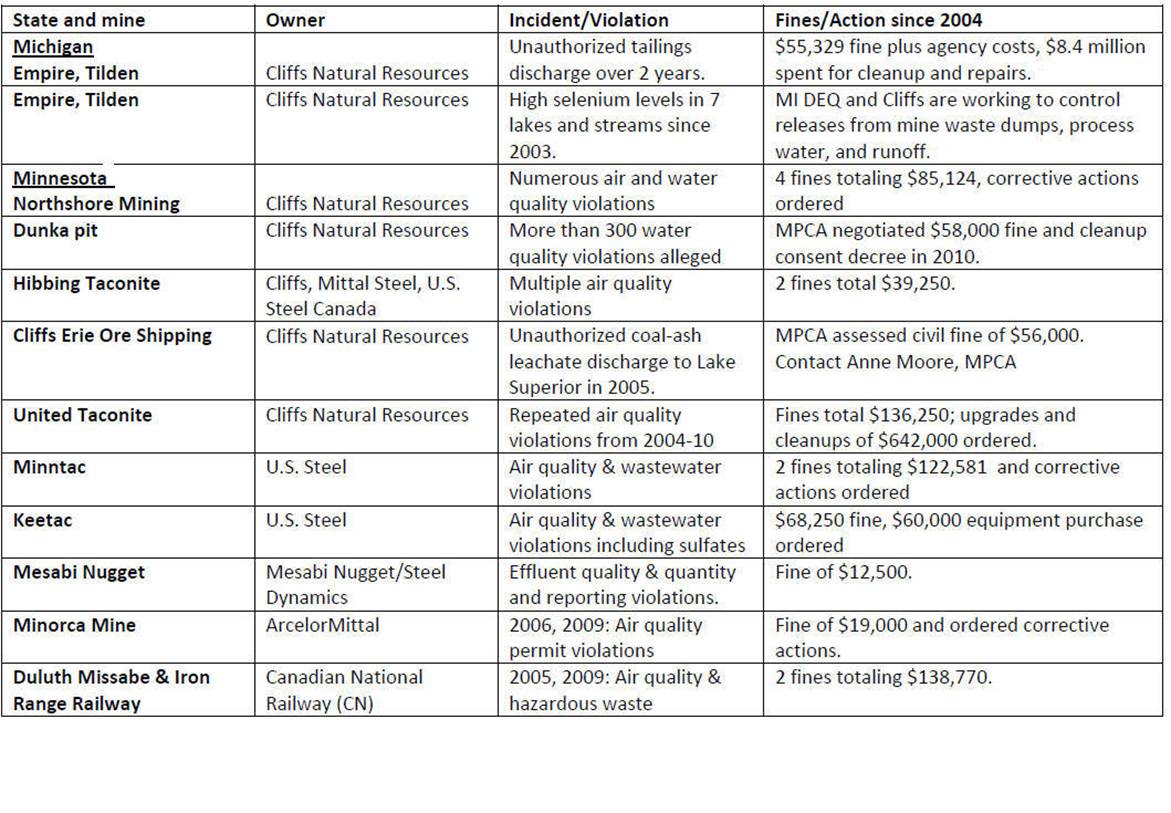

Nine taconite mines and related production and transport facilities in Minnesota and Michigan (seven in MN, two in MI) account for nearly all U.S. iron ore production. The chart below shows dozens of air and water quality violations resulting in more than $790,000 in fines plus cleanup orders and stipulations costing another $9.1 million.

The facts show all modern U.S. Taconite mines have violations and fines since 2004:

One claim to support special laws for taconite mining is that iron ore does not cause acid mine drainage from mining in sulfide ores. There are two reasons why this claim should be rejected. First, there have been serious acid mine drainage issues with at least two iron ore mines: the Dunka Pit in Minnesota (see chart above) where uncontrolled acid drainage has been discharging into streams leading to Birch Bay since the 1960’s. The Dober and Buck mines in Michigan killed aquatic life in 7 miles of the Iron River and damaged 10.5 miles of the Brule River. The Hanna Corporation was fined $368,000 for the damage there in 1997.

The second reason for rejecting this claim is that there is no science to back up assertions that the iron ore in the Penokee Range will not cause acid. WI State Geologist, Jamie Robertson commented about the acid potential for this ore, “We know very little about the details of the iron ore, of the immediately adjacent wasterock, of the sampling that was done years ago.” It is irresponsible to draft new laws that use this claim as fact without science to support it.

The track record of regional taconite mining instructs Wisconsin on what should be expected if a mine is permitted here. Air and water quality in northern Wisconsin would be harmed by mining waste dust from tailings, waste rock, ore transportation and ore processing, which produce contaminants such as mercury, arsenic, and other heavy metals, sulfates, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides. These last two contaminants combine to help form acid rain, while high concentrations of sulfates harm native wild rice. In Minnesota, current and historic mining are a major source of sulfates to waterways.

A Minnesota DNR report in 2003 found that taconite mining is the 2nd largest source of mercury emissions after coal power plants. The study also reported that no suitable technology has been found to curtail taconite mercury emissions. A taconite mine here will be a new source of mercury that will only further contaminate and poison our fish and wildlife when our lakes are already under advisories against consuming mercury contaminated fish.

Transporting taconite ore causes pollution too. One example is the Duluth Missabe and Iron Range Railway in Minnesota which has been cited for multiple violations of hazardous waste restrictions and air quality and fined $138,770 for violations occurring in 2005 and 2009.

If existing taconite mining cannot be counted on for examples of safe mining, what about GTAC’s track record? GTAC itself has never mined taconite before but GTAC’s owners- the Cline Groupoperate coal mines in Illinois. Cline has been cited 25 times for violating water quality standards at 4 mines including 19 times at the Deer Run Mine which opened only 3 years ago.

Prepared by the Sierra Club, Oct. 2011. More info at: wisconsin.sierraclub.org/PenokeeMine.asp

Water pollution law suit for Cleveland Cliffs

Three groups recently announced their intent to file a lawsuit against Cliffs Erie, a subsidiary of Cliffs Natural Resources, for ongoing water pollution from previous taconite iron mining at three sites on Minnesota’s Iron Range. PolyMet Mining Co. plans to utilize two of the sites in order to dispose of wastes from its proposed metallic-sulfide NorthMet project. As part of a purchase agreement, Cliffs would maintain a roughly 7% stake in the project. The other Cliffs site, at the old Dunka Mine, is closer to Franconia Minerals and Duluth Metals’ proposed sulfide projects.

A news release issued by the Center for Biological Diversity noted that, “according to Cliffs Erie’s own monitoring reports, there are numerous ongoing violations of water-quality laws relating to management of the former LTV tailings basin. PolyMet’s proposal for its copper-nickel mine is to pile its own tailings waste on top of those from a former taconite mine that are still polluting.”

The Center for Biological Diversity, Save Lake Superior Association, and the Indigenous Environmental Network filed a formal notice letter today that acts as a “prerequisite to filing a citizen enforcement action under the Clean Water Act.” The Save Lake Superior Association, a grassroots citizen group, proved instrumental in holding the Reserve Mining Co. to account for dumping iron mining waste into Lake Superior from 1955 into the 1970s. The pollution introduced asbestos-like material into the lake and harmed fishing in the area.

From a recent Center for Biological Diversity news release:

“Before the state even considers the approval of a new wave of mining in northeastern Minnesota, it should first require the mining companies to clean up the pollution from past taconite mines,” said Marc Fink, an attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity. “As we all learned as kids, you should clean up one mess before making another one.”

The LTV basin, located six miles north of Hoyt Lakes, was used for taconite tailings from the 1950s until 2001. The unlined basin is the source of numerous seeps and discharges of polluted wastewater into groundwater and surface waters, which eventually reach the Embarrass River. For the proposed NorthMet mine, PolyMet proposes to process more than 225 million tons of ore at the LTV processing facility, and use the same LTV tailings basin already known to be leaking.

“While past mining has already polluted these waters, the proposed heavy metals mining would bring severe new threats of pollution to these waters, which ultimately flow into Lake Superior at the Duluth harbor,” said Le Lind of the Save Lake Superior Association. “This new threat includes sulfuric acid runoff and higher levels of mercury.

Four treatment methods for new copper mine in Michigan

Anderson identifies four treatment methods, each with its own benefits and drawbacks and some better at dealing with certain contaminants than others.

Biological treatment—the method Cliffs Erie just got sued over and which the MPCA identifies as a "long–term" and "passive" solution for PolyMet—involves the creation of large wetlands covered with mats of woven reeds and grasses.

"It is so profound and huge, it’s kind of exciting," says Anderson. "But you can’t just set these up and walk away from them."

The grasses consume oxygen as they decay, producing carbon. When wastewater contaminated with mercury and sulfates is then added, all the elements for methylation are present and the mats must be continually disposed of as hazardous waste. This successfully gets rid of mercury—but by producing methyl mercury instead.

Clark and Pribble at the MPCA hedged on the question of whether mercury standards are considered met if mercury is disappearing because it’s becoming the much more dangerous methyl mercury. "Our water quality standards include mercury," says Clark, "so that would be our absolute standard…The standard [1.3 nanograms per liter] is built on the process that if you reduce the mercury, you’ll reduce the methyl mercury."

When pressed as to whether mercury methylation would, technically, count as a reduction in elemental mercury itself, Pribble responded, "No. We’re considering what comes out of the pipe or stack. If you’re cutting off the mercury, then it’s not there to convert to methylated mercury."

The biggest whopper so far, judging by Anderson’s information. "The methylation downstream has virtually nothing to do with the small amount of mercury they will be releasing. It has to do with the large amount of sulfate they will be releasing. The mercury is legacy mercury in the sediments from the last 100 years."

In the short–term, Clark says PolyMet is proposing a chemical precipitation treatment at the mine site and reverse osmosis for discharge at the tailings site, both of which are "capital and labor intensive."

Chemical precipitation, which Anderson describes as "do–able," involves introducing a chemical specific to each contaminant, causing them to precipitate, or drop out of the solution. "Then you can scoop that up and take it to a landfill. The sulfate is going to be as harmless as Epsom salts." Some contaminants could be safely re–used. However, the system "needs to be monitored 24 hours a day, forever" and some of the chemicals, before they’re introduced, are highly toxic.

Reverse osmosis, proposed for tailings discharge, is a combination of two methods effective for sulfates—ion exchange and membrane treatment. Being an ion, sulfate has an electrical charge. Electricity can be introduced to collect the sulfates for removal and disposal. However, the electricity (and the coal to generate it) is costly and this method, too, must be continued indefinitely.

In membrane treatment, contaminated water is passed through polymer sheets, which is "good for sulfates, but not as good for other contaminants. That’s going to be pretty bad water coming out of that membrane."

Then there’s the matter of natural precipitation, which Anderson says is difficult—though not impossible—to contain, as rain and snow fall on hundreds of acres of open mine pits, tailings ponds, and waste rock piles, washing sulfates into the groundwater.

But the MPCA doesn’t seem particularly concerned about this. "As far as the scale of the project," says Pribble, "that’s not a limitation. As far as the precipitation, there would be a system to handle that."

"They’re proposing temporary stock piles before it’s taken care of completely," says Clark, "liners under their temporary stock piles that prevent runoff from infiltrating into the ground.

"The way the project is designed, any precipitation, any water that touched that rock, will be captured and treated." He says the system is based on "peak flows and worst–case scenarios."