CATER Mask

Decisions

December 8, 2020

Masks

will be Needed to Cope with PM from Road Traffic

Tire Wear

Mask Wearing Should be Coordinated with Ambient

Air Pollution Levels but We Have to Scrutinize

the Definitions

Purar Offers Reusable Mask With Unique Features

Don’t Confuse Medical with

Public Health Guidance

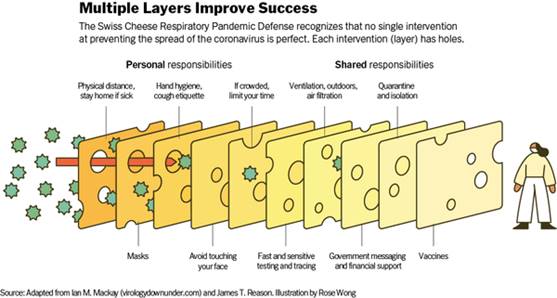

Mask and Filter

Protection are Part of a Swiss Cheese Defense

Program

__________________________________________________________________________

Masks will be Needed to Cope with PM from Road

Traffic Tire Wear

OECD has just issued a report predicting that

wear and tear from brakes, tires and road

surfaces will soon overtake car exhaust fumes as

the leading source of fine particles released

into the air by road traffic, according to a new

OECD report. Heavy electric vehicles with

long-distance batteries could compound the

problem even as they slash emissions from engine

exhaust.

The findings in

Non-exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road

Transport: An ignored Environmental Policy

Challenge

suggest that electric vehicles should not be

exempted from tolls and congestion charges aimed

at reducing road traffic emissions. Instead,

road traffic regulations should consider both

exhaust and “non-exhaust” emissions from all

vehicles and should take into account factors

like vehicle weight and tire composition. Policy

makers should also favor measures that reduce

driving distances, limit urban vehicle access

and encourage public transport, walking and

cycling.

Exposure to airborne particulate matter (PM) is

associated with acute respiratory infections,

lung cancer, and chronic respiratory and

cardiovascular diseases. Road traffic is behind

a quarter of PM2.5, the most damaging type, in

urban areas yet only exhaust emissions of PM are

regulated. No standards exist for measuring or

regulating non-exhaust PM emissions.

As particulate matter emitted from exhaust

sources decreases with the uptake of electric

vehicles, the majority of PM released into the

air by road traffic could come from non-exhaust

sources as early as 2035.

The amount of non-exhaust particulate matter a

vehicle emits is determined by many factors,

including vehicle weight, driving styles, the

material composition of brakes, tires and roads,

and the amount of dust on road surfaces.

Lightweight electric vehicles with a driving

range of about 100 miles (161 km) emit an

estimated 11-13% less PM2.5 than conventional

vehicles in the same segment. However, heavier

electric vehicles with battery packs enabling a

range of 300 miles (483 km) emit an estimated

3-8% more PM2.5 than equivalent conventional

vehicles.

The report finds that the total amount of

non-exhaust particulate matter emitted by

passenger vehicles worldwide is likely to rise

by 53.5% by 2030.

These findings underline the need to establish

standardised approaches to measuring non-exhaust

particulate matter and to develop a better

understanding of how factors like vehicle

characteristics influence the amount of PM

generated, the report says.

Download the

report :

Non-exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road

Transport

Download a

summary of key messages:

Non-exhaust Emissions Highlights

Watch a

discussion with the report’s authors

live at 16:00 CET or on replay

For further information journalists are invited

to contact

Catherine Bremer

in the OECD Media Office (+33 1 45 24 80 97).

Mask Wearing Should be Coordinated with Ambient

Air Pollution Levels but We Have to Scrutinize

the Definitions

The definitions of air pollutant quantities are

based on tradition and are often not the most

accurate selections. Sensor based ambient air

monitors are less costly than analyzers or

permanent samplers but there has been question

about their accuracy. Dubai solved this problem

with a mobile EPA qualified analyzer system and

14 sensor-based systems. China has installed

10,000 Sail Hero sensor-based systems that

correlate closely with analyzers for each of the

major pollutants. The regulations relative to

toxic metals require polluters only to limit PM2.5 which

is used as surrogate for toxic metals. This is

despite the fact that some metals are 100,000

times more toxic than others. This is despite

the fact that the employment of multi metals

analyzers in a St. Louis ambient monitoring

program showed that levels of certain highly

toxic metals varied depending on the wind

direction.

As a St Louis citizen you felt safe not wearing

a mask outside when PM 2.5 levels were low.

However, a lead smelter south west of the City

transmits dangerous levels of lead to the city

when the wind is blowing at certain speeds and

direction. It only takes a tiny fraction of lead

in the PM 2.5 to make inhalation risky.

Opacity is still used for regulatory purposes.

Its origin was long before scrubbers were

employed after the particulate collector. In

most cases scrubbers provide additional

particulate removal but, in some cases, when

they malfunction, they increase particulate

discharges. But believe it or not opacity

regulations require measurement prior to the

scrubber since opacity cannot be measured in a

wet stack.

Power plants and other combustion sources are

required to limit their emissions of gas phase

mercury. This is based on the fact that prior to

attempted control mercury is in the gas

phase. However, when activated carbon is

injected, the mercury becomes attached to

particles. If these particles are not captured,

they can fall in the vicinity of the plant. In

contrast gas phase mercury may travel across

continents. It is therefore possible that

mercury control could result in greater mercury

contamination near the source than if there were

no controls. Permanent samplers will capture

particulate mercury but can be modified to

segment the particulate and gas phase. The

Cooper mercury analyzer also measures total

mercury. Doesn’t it make sense to regulate

total mercury?

The fundamental principles are also murky.

Particulate is defined as the diameter of a

sphere and the particle weight is assumed. In

fact, particles are not spheres and their

specific gravity varies. The cascade impactor is

used to determine particle size. But it creates

its own definition which does not magically

transform hair shaped particles into spheres of

equal gravity.

The McIlvaine Company identified this problem

relative to the sizing of wet high energy

particulate scrubbers based on particle size.

Purchasers who relied on particle size analyses

in many cases experienced disastrous results.

McIlvaine addressed this problem with the

invention of the McIlvaine mini scrubber. It is

a 1 CFM device where the energy in the turbulent

zone can be varied and the results determined in

mg/m3.

The impact of ambient particulate could be

addressed in a similar manner. A miniature lung

equivalent could be used to determine how much

penetrates and how much is captured on the

surface. It is likely that cascade impactor

measured particles of 2.5-micron diameter

penetrate differently. So, the new definition

would be particles which penetrate the lungs vs

those which do not.

EPA standards for ambient measurement of

pollutants have been adopted around the world.

But when China and Dubai use methods which may

be equally indicative even if they don’t

correlate 100% with EPA methods, there is

eventually going to be a movement toward a new

standard.

Toxic metals need to also be addressed. The

concern is not only the particle penetration

aspect but the toxicity. There are now multi

metals analyzers which can measure the

concentration of 17 different metals. So, the

lung penetration index could also be adjusted

based a toxic metal harm quotient. In St. Louis

when winds blow from the south, consistent with

the bearing of the Doe Run Herculaneum lead

smelter the toxic metal harm index is likely to

be much higher than would be reflected by PM2.5 measurement.

McIlvaine has long promoted the use of a toxic

metal harm metric which would consider the

relative contribution of each metal. This would

be of more benefit to St Louis citizens. This

common metric can be expanded to all pollutants

and be a much better guide as to whether to

remain indoors. This is explained at Sustainability

Universal Rating System.

Purar Offers Reusable Mask With Unique Features

Your air, your style, and you. Breathe in

healthy and clean air with Purar, where the

useful is separated from the harmful particles

by providing all with comfortable, highly

functional, and appealing face masks, while

never compromising on personal style.

Having experienced Shanghai China’s long season

of air pollution first hand, Purar’s co-founder,

Jasmine/Xiaohua Meng, found that wearing a mask

was the only way to protect yourself. As a daily

mask user, she experienced the discomfort of

wearing standard surgical facemasks, which make

breathing harder from increased humidity, fogs

up glasses, and can irritate the wearer.

With the question in mind of finding a highly

protective, comfortable, and stylish

alternative, Jasmine delivered the pitch to her

employer, Mann+Hummel, which makes most of its

billions annually from industrial air filter

manufacturing; conventional car filters, to be

specific. Headquartered near Stuttgart, Germany,

Mann+Hummel has been looking for alternative

directions to pivot into, given that the

conventional car market is changing

dramatically. So a few years ago, Mann+Hummel

launched a startup contest called InCube, the

winning idea gets you six months at a startup

incubator, Plug and Play Tech Center, in

California.

Purar emerged as a winning product for the 2019

contest and was formally launched in the Plug

and Play’s Acceleration program in Silicon

Valley, with a global team of developers working

to create a mask that not only works well, but

also feels like a seamless part of our wearers.

Derived from the words “Pure Air”, the facemasks

are engineered by the filtration experts at

Mann+Hummel to achieve the KN95’s filtration

level, giving it the ability to filter more than

95% of the 0.3 micron particles. Besides being

certified for KN95 standards, Purar facemasks

has also passed the leakage test according to

GB2626-2019.

In terms of the design, the reusable facemask

includes a filter that can be replaced and a

sustainable outer shell which is washable. The

washable shell is crafted with an ergonomic

design that is configured carefully with

polygons for fitting comfortably according to

your face shape. An additional feature of the

mask is the neck grip that does not hurt your

ears as much as ear-looped mask. This neck grip

provides more convenience for wearers who use

wire or wireless audio device such as headphone

or AirPods or even female wearers who

accessorize their ears with large chunky

earrings. For those who wear glasses, the mask

comes with a pre-formed nose support that helps

prevent glass-fogging issues.

Each mask is available in 2 sizes (size S and L)

and includes 6 stylish colors: Blue, Black,

Burgundy, Grey, Pink and Mauve. A box of mask

retails at USD49 and comprises of a mask shell,

2 replaceable filters (Protect Plus and Lite

Comfort) and a travel pouch. Protect Plus filter

is tested and certified for standard that

similar to American N95 (GB2626-2019,

certification KN95) to provide full protection.

Whilst Lite Comfort filter provides higher air

permeability than Protect Plus to provide more

comfort and breathability.

Purar mask is available in 6 stylish colors:

Blue, Black, Burgundy, Grey, Pink and Mauve

Purar does not stop at just offering a highly

fashionable facemask to end-consumers, it goes

beyond this by also offering customizable mask

for B2B corporate needs. After all, Purar’s

mission is to provide people with a comfortable

and fashionable accessory by leveraging the

creativity of young designers to enable them to

breathe cleaner air.

Customizable facemask for corporate needs

Don’t Confuse Medical with

Public Health Guidance

Michael Mina

of Harvard says it is important to distinguish medical from public

health guidance. This is good

advice. In fact it is important to also

distinguish guidance for vaccine manufacture.

It is also desirable to distinguish between sub

segments. The guidance for personnel entering an

isolation unit are far different than for a

person at the registration desk in a hospital.

|

Application |

Filtration Efficiency % |

|

Medical |

|

|

Registration |

90 |

|

Non infectious |

95 |

|

Infectious |

99.99 |

|

Pharmacy |

99.99 |

|

Vaccine Mfg. |

|

|

Fill and finish |

99.999 |

|

Adjacencies |

99.9 |

|

Public High Positivity Zone |

|

|

Open Parks |

60 |

|

City Streets |

90 |

|

Elevators |

95 |

|

Subways |

99 |

The efficiency needs can be achieved with a

combination of filters and masks. If there are

filter cubes on the city streets at

intersections the need for more efficient masks

is less. If the elevator has a HEPA filter and

laminar air flow there is less of a burden on

the mask. This combination of filters can be

conceived as the swiss cheese defense program as

explained below.

Mask and Filter Protection

are Part of a Swiss Cheese Defense Program

This concept was the basis of an article by Siobhan

Roberts

published Dec. 5, 2020

in the NY Times.

Lately, in the ongoing

conversation about how to defeat the coronavirus,

experts have made reference to the “Swiss cheese

model” of pandemic defense.

The metaphor is easy enough

to grasp: Multiple layers of protection,

imagined as cheese slices, block the spread of

the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that

causes Covid-19. No one layer is perfect; each

has holes, and when the holes align, the risk of

infection increases. But several layers combined

— social distancing, plus masks, plus

hand-washing, plus testing and tracing, plus

ventilation, plus government messaging —

significantly reduce the overall risk.

Vaccination will add one more protective layer.

“Pretty soon you’ve created an impenetrable

barrier, and you really can quench the

transmission of the virus,” said Dr. Julie

Gerberding, executive vice president and chief

patient officer at Merck, who recently

referenced the Swiss cheese model when speaking

at a virtual gala fund-raiser for MoMath, the

National Museum of Mathematics in Manhattan.

“But it requires all of those things, not just

one of those things,” she added. “I think that’s

what our population is having trouble getting

their head around. We want to believe that there

is going to come this magic day when suddenly

300 million doses of vaccine will be available

and we can go back to work and things will

return to normal. That is absolutely not going

to happen fast.”

Rather, Dr. Gerberding said in a follow-up

email, expect to see “a gradual improvement in

protection, first among the highest need groups,

and then more gradually among the rest of us.”

Until vaccines are widely available and taken,

she said, “we will need to continue masks and

other common-sense measures to protect ourselves

and others.”

In October, Bill Hanage, an epidemiologist at

the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health,

retweeted an infographic rendering

of the Swiss cheese model, noting that it

included “things

that are personal *and* collective

responsibility — note the ‘misinformation mouse’

busy eating new holes for the virus to pass

through.”

“One of

the first principles of pandemic response is, or

ought to be, clear and consistent messaging from

trusted sources,” Dr. Hanage said in an email.

“Unfortunately the independence of established

authorities like the C.D.C. has been called into

question, and trust needs to be rebuilt as a

matter of urgency.” A catchy infographic is a

powerful message, he said, but ultimately

requires higher-level support.

The Swiss cheese concept originated with James

T. Reason, a cognitive psychologist, now a

professor emeritus at the University of

Manchester, England, in his 1990 book, “Human

Error.”

A succession of disasters including

the Challenger shuttle explosion, Bhopal and

Chernobyl — motivated the concept, and it became

known as the “Swiss cheese model of accidents,”

with the holes in the cheese slices

representing errors that

accumulate and lead to adverse events.

The model has been widely used by safety

analysts in various industries, including

medicine and aviation, for many years. (Dr.

Reason did not devise the “Swiss cheese” label;

that is attributed to Rob Lee, an Australian

air-safety expert, in the 1990s.) The model

became famous, but it was not accepted

uncritically; Dr. Reason himself noted that it

had limitations and was intended as a generic

tool or guide. In 2004, at a workshop addressing

an aviation accident two years earlier near

Überlingen, Germany, he delivered a talk with

the title, “Überlingen: Is Swiss cheese past

its sell-by date?”

In 2006, a review of the model, published by

the Eurocontrol

Experimental Center, recounted that Dr.

Reason, while writing the book chapter “Latent

errors and system disasters,” in which an early

version of the model appears, was guided by two

notions: “the biological or medical metaphor of

pathogens, and the central role played by

defenses, barriers, controls and safeguards

(analogous to the body’s autoimmune system).”

The cheese metaphor now pairs fairly well with

the coronavirus pandemic. Ian M. Mackay, a

virologist at the University of Queensland, in

Brisbane, Australia, saw a smaller version on Twitter,

but thought that it could do with more slices,

more information. He created, with

collaborators, the “Swiss

Cheese Respiratory Pandemic Defense” and

engaged his Twitter community, asking for

feedback and putting the visualization through

many iterations. “Community engagement is very

high!” he said. Now circulating widely, the

infographic has been translated into

more than two dozen languages.

“This multilayered approach

to reducing risk is used in many industries,

especially those where failure could be

catastrophic,” Dr. Mackay said, via email.

“Death is catastrophic to families, and for

loved ones, so I thought Professor Reason’s

approach fit in very well during the circulation

of a brand-new, occasionally hidden, sometimes

severe and occasionally deadly respiratory

virus.”

The following is an edited version of a recent

email conversation with Dr. Mackay by the

Washington Post.

Q. What does the Swiss cheese model show?

A. The real power of this infographic — and

James Reason’s approach to account for human

fallibility — is that it’s not really about any

single layer of protection or the order of them,

but about the additive success of using multiple

layers, or cheese slices. Each slice has holes

or failings, and those holes can change in

number and size and location, depending on how

we behave in response to each intervention.

Take masks as one example of a layer. Any mask

will reduce the risk that you will unknowingly

infect those around you, or that you will inhale

enough virus to become infected. But it will be

less effective at protecting you and others if

it doesn’t fit well, if you wear it below your

nose, if it’s only a single piece of cloth, if

the cloth is a loose weave, if it has an

unfiltered valve, if you don’t dispose of it

properly, if you don’t wash it, or if you don’t

sanitize your hands after you touch it. Each of

these are examples of a hole. And that’s in just

one layer.

To be as safe as possible, and to keep those

around you safe, it’s important to use more

slices to prevent those volatile holes from

aligning and letting virus through.

Q. What have we learned since March?

A. Distance is the most effective intervention;

the virus doesn’t have legs, so if you are

physically distant from people, you avoid direct

contact and droplets. Then you have to consider

inside spaces, which are especially in play

during winter or in hotter countries during

summer: the bus, the gym, the office, the bar or

the restaurant. That’s because we know

SARS-CoV-2 can remain infectious in aerosols

(small floaty droplets) and we know that aerosol

spread explains Covid-19 superspreading events.

Try not to be in those spaces with others, but

if you have to be, minimize your time there

(work from home if you can) and wear a mask.

Don’t go grocery shopping as often. Hold off on

going out, parties, gatherings. You can do these

things later.

Q. Where does the “misinformation mouse” fit in?

A. The misinformation mouse can erode any of

those layers. People who are uncertain about an

intervention may be swayed by a loud and

confident-sounding voice proclaiming that a

particular layer is ineffective. Usually, that

voice is not an expert on the subject at all.

When you look to the experts — usually to your

local public health authorities or the World

Health Organization — you’ll find reliable

information.

An effect doesn’t have to be perfect to reduce

your risk and the risk to those around you. We

need to remember that we’re all part of a

society, and if we each do our part, we can keep

each other safer, which pays off for us as well.

Another example: We look both ways for oncoming

traffic before crossing a road. This reduces our

risk of being hit by a car but doesn’t reduce it

to zero. A speeding car could still come out of

nowhere. But if we also cross with the lights,

and keep looking as we walk, and don’t stare at

our phone, we drastically reduce our risk of

being hit.

We’re already used to doing that. When we listen

to the loud nonexperts who have no experience in

protecting our health and safety, we are

inviting them to have an impact in our lives.

That’s not a risk we should take. We just need

to get used to these new risk-reduction steps

for today’s new risk — a respiratory virus

pandemic, instead of a car.

Q. What is our individual responsibility?

A. We each need to do our part: stay apart from

others, wear a mask when we can’t, think about

our surroundings, for example. But we can also

expect our leadership to be working to create

the circumstances for us to be safe — like

regulations about the air exchange inside public

spaces, creating quarantine and isolation

premises, communicating specifically with us

(not just at us), limiting border travel,

pushing us to keep getting our health checks,

and providing mental health or financial support

for those who suffer or can’t get paid while in

a lockdown.

Q. How can we make the model stick?

A. We each use these approaches in everyday

life. But for the pandemic, this all feels new

and like a lot of extra work. Because everything

is new. In the end, though, we’re just forming

new habits. Like navigating our latest phone’s

operating system or learning how to play that

new console game I got for my birthday. It might

take some time to get across it all, but it’s

worthwhile. In working together to reduce the

risk of infection, we can save lives and improve

health.

And as a bonus, the multilayered risk reduction

approach can even decrease the number of times

we get the flu or a bad chest cold. Also,

sometimes slices sit under a mandate — it’s

important we also abide by those rules and do

what the experts think we should. They’re

looking out for our health.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/05/health/coronavirus-swiss-cheese-infection-mackay.html